Coal: Part I

The Black Rock That Built Our World

How a black rock formed from ancient swamps became the foundation of modern civilization—powering the Industrial Revolution, reshaping cities, and creating the electrical grid that still defines our lives today.

Bituminous coal—the dense, energy-rich fuel that transformed human civilization and enabled the industrial age.

If you were bad this year, you might have found a lump of coal in your stocking. But why is this black rock a punishment? For centuries, it was the ultimate gift: a dense, portable store of ancient sunlight that promised heat, light, and industrial might. Coal is the story of abundance, of capitalism, of the very foundations of the modern world.

This is a story of a step change, a transformation so profound it reshaped the course of human history. To understand our world today—from the systems that power our lives to the climate crisis we now face—you must first understand coal. We are in the middle of upgrading so much of our world, and studying the history of these massive shifts provides the best resource to understand what worked, what didn't, and the human effort required to build our reality.

Our journey leans heavily on the foundational work of Barbara Freese, whose 2003 book, *Coal: A Human History*, serves as the backbone for this story. We'll trace the epic arc of this simple rock, from its primordial origins in bizarre, swampy forests to its role in building—and threatening—our civilization. We'll uncover how ancient plants locked away the carbon that powered empires, how the race for coal laid the groundwork for modern industry, and how this revolution came at a staggering human and environmental cost.

You might think of coal as a relic, but it is far from a closed chapter of history. The world used more coal in 2023 than in any other year, primarily for electricity generation and as a key ingredient for steel and cement. The combustion of coal remains the largest single source of global CO2 emissions. Though this story is rooted in the past, its echoes are all around us today.

The Carboniferous Genesis (400 Million Years Ago)

Peat gathering represents humanity's earliest use of fossilized plant matter as fuel. Over millions of years, compressed peat became the coal that would power the Industrial Revolution.

To find the origin of coal, you must travel back long before the rise of industrial London, before humans, even before the dinosaurs. Our journey begins 400 million years ago in the Carboniferous Period, a time when the Earth was a vastly different and almost alien world. Continents were mashed together in the supercontinent of Pangea, and life was exploding in scale.

A World of Giants

This was an era of giants, fueled by an atmosphere thick with oxygen—around 35%, compared to today's 21%. This super-oxygenated air allowed dragonflies to grow wingspans of three feet and millipedes to reach the height of a human. It was a wild time on planet Earth, defined by sprawling, swampy forests filled with ferns boasting 30-foot-wide trunks.

We named this 100-million-year epoch the Carboniferous Period, which in Latin literally means "coal-bearing." Despite all the incredible evolutionary changes happening, the defining feature for humanity, looking back, was that this was the time that gave us coal. What we now know as the great coal centers of the world—Newcastle in England, Pennsylvania in the U.S., Inner Mongolia in China—were then tropical, swampy regions clustered around the equator.

The Making of a Fuel

As these massive plants died, they fell into the swamps. Submerged in water, they couldn't fully decompose and release their stored carbon into the atmosphere. Instead, the carbon remained trapped. Over millions of years, layers of dead plants, water, and sediment piled up, compressing the organic matter under immense weight and pressure.

The first stage of this transformation creates peat, a dark, soil-like material resembling coffee grounds. Peat itself became a fuel source, famously used in Scotland to dry malt for Scotch whisky, giving it a distinctive smoky flavor. Today, the world's peatlands still hold a massive 550 gigatons of carbon, making them one of the planet's largest carbon sinks.

As millions of years passed and the pressure mounted, more water and volatile gases were squeezed out, leaving behind an increasingly pure, dense carbon. This process created a spectrum of coal types, from soft, crumbly lignite to the harder bituminous coal. In regions where continental collisions created mountain ranges like the Appalachians, the intense pressure forged the hardest, purest form of all: anthracite, a shiny, almost crystalline rock that is 95-100% carbon.

Early Sparks, Ancient Use (25,000 BCE – 1300 CE)

For thousands of years after Homo sapiens discovered how to burn wood, coal remained a geological curiosity. Yet, in scattered pockets across the globe, early humans found these strange black rocks and learned they could burn. The earliest known use dates back to 25,000 BCE in the modern-day Czech Republic, where archaeological evidence shows a settlement using coal for fuel.

A Global Curiosity

Evidence of early use appears across civilizations. In China, surface mining for household heating occurred as early as 3500 BCE. Around 370 BCE, the Greek philosopher Theophrastus, a student of Aristotle, wrote of a stone that "burns like charcoal" and was used by metalworkers. The Aztecs used it for fuel and even carved the black stone into jewelry.

During their occupation of Britain, the Romans used coal to heat public baths and villas, and occasionally for smelting iron. However, after the Romans departed around 400 CE, coal use largely faded into obscurity in Britain until its revival in the 12th century. The most significant early adoption, however, was happening far to the east.

Marco Polo's Magic Stone

In the late 13th century, the Italian explorer Marco Polo spent 17 years in China, a civilization far more advanced than Europe at the time. When he returned, he brought back astonishing accounts of their widespread use of coal, a technology that shocked his European counterparts. This early adoption was likely driven by regional firewood scarcity, a pattern that would repeat itself across the world.

Polo wrote of "a kind of black stone... which they dig out and burn like firewood." He observed, "If you supply the fire with them at night... you will find them still alight in the morning," marveling at this "magic stone" that could burn all night. This abundant fuel helped make China the world's largest iron producer during this era, centuries before Europe would unlock the same potential.

The Black Death and a King's Frustration (1200 – 1550)

Back in Britain, the stage was being set for coal's dramatic ascent. A crucial legal precedent was established in 1217 with the Forest Charter, a companion to the Magna Carta. This document granted landowners rights to the resources on their land, including minerals. While not a major concern at the time, this charter meant that whoever owned the land, owned the coal beneath it.

The Church's Monopoly

Ironically, much of the land in what would become Britain's most vital coal region, Newcastle, was not owned by private individuals but by the Roman Catholic Church. The Church controlled the digging, production, and output of the early coal trade. In a strange twist of history, the first coal barons were bishops, monks, and nuns, who oversaw the labor of serfs on their lands.

The Black Death intervened. The plague of 1347-1351 killed one in three Europeans and halved England's population, from six million to less than three million by 1400. London, a bustling city of 100,000, shrank to just 25,000 in a single generation. Suddenly, the immense pressure on forests for firewood eased, and with fewer people, the demand for fuel plummeted, delaying coal's rise for over a century.

Henry VIII's Inadvertent Gift

Had the Church retained its lands, coal may never have taken off. The clergy had little interest in investing in risky new mining technologies. But in 1527, King Henry VIII's marital frustrations inadvertently accelerated the transition. Furious that Pope Clement VII would not grant him an annulment from Catherine of Aragon, Henry broke with Rome and seized the Church's assets.

With this single act, Henry dissolved the monasteries and transferred a fifth of the nation's land and wealth—including the crucial coal fields of Newcastle—from the Church to the Crown. This land was then sold off to private individuals and entrepreneurs. These new owners, unlike the Church, were hungry for profit and willing to invest in the difficult and dangerous work of extracting coal from the earth, setting the stage for an energy revolution.

The Domestic Revolution (1550 – 1700)

As England's population recovered in the 1500s, the wood shortage returned with a vengeance, creating a crisis akin to a modern gas shortage. The crisis was amplified by a climactic shift known as the "Little Ice Age," one of the coldest periods since the last true ice age. Wood was essential for heating homes and cooking food; it literally kept people alive. As forests vanished and prices soared, people needed an alternative.

London's Coal Boom

This was the moment coal made its leap from a niche industrial fuel to the heart of domestic life. London's coal consumption exploded, soaring from about 15,000 tons per year in the early 1500s to nearly 500,000 tons by the 1650s—a more than 30-fold increase. For many households, coal became a lifeline, but it was an expensive one, consuming anywhere from 10 to 50% of a family's income.

The public's dependence on this new fuel was absolute. When supply chains faltered or prices spiked, the population came to the brink of violence, terrified of "fuel famines." Early complaints about London's foul, smoky air emerged, but for most, the fear of freezing to death far outweighed concerns about pollution. People would accept dirty air if it meant they could have the energy they needed to survive.

The Age of the Chimney

This fuel switch triggered a radical transformation inside the English home. Unlike wood, coal couldn't simply be burned in an open hearth in the middle of a room; it required a grate for airflow and produced a heavy, acrid smoke that didn't rise easily. This necessity drove the widespread adoption of a relatively new technology: the chimney. While a few existed in the 1550s, by the end of the century, they were commonplace in London.

This architectural shift had a surprising ripple effect. Chimneys created a strong, cold draft along the floor, making the ground level, once a cozy place to sit and sleep, uncomfortably chilly. This led to another innovation: furniture with legs. People needed elevated chairs to sit on and raised beds to sleep in, simply to escape the cold floor. The fuel you used suddenly determined the design of your home and the very furniture you owned.

Iron's Fiery Embrace (1678 – 1780)

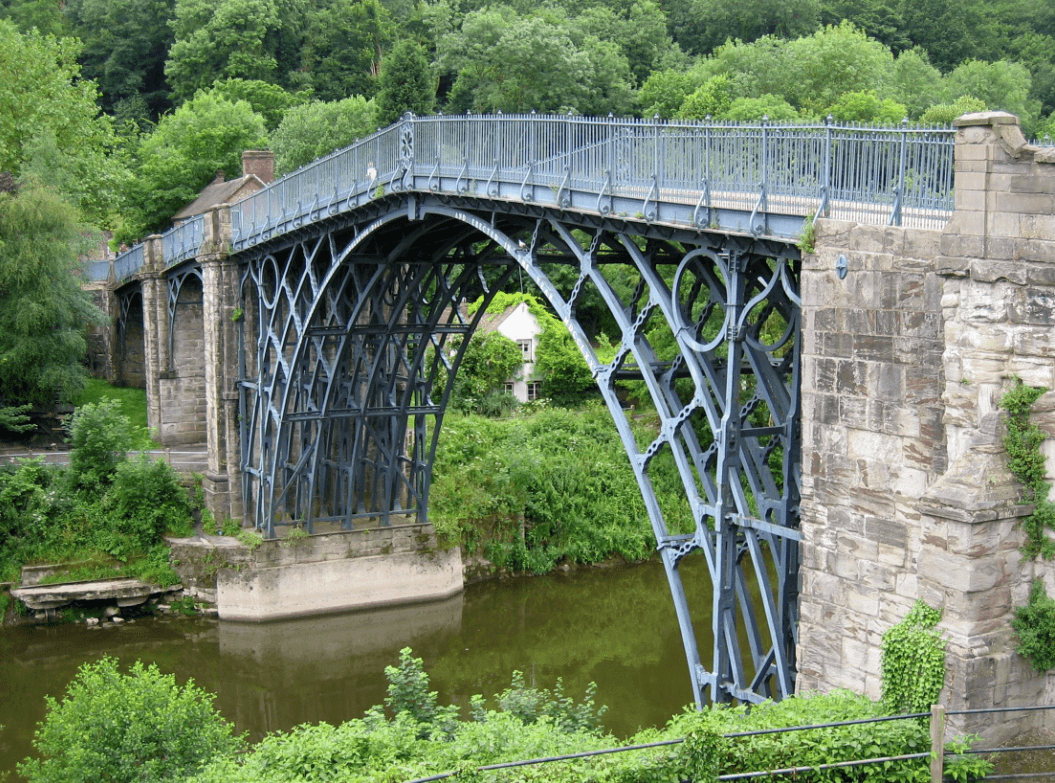

The Iron Bridge at Coalbrookdale (1779) was the first major structure built from cast iron, made possible by Abraham Darby's coal-powered coke furnaces. It stands as a monument to the Industrial Revolution.

The transition to coal hit a major snag in the kitchen. The hotter, sulfurous flames of a coal fire would crack and destroy the common brass and copper pots of the era. The ideal replacement was thick, durable cast iron, but this presented a paradox: making cast iron required vast amounts of charcoal, which was made from the very wood that England no longer had.

Abraham Darby and the Coke Revolution

The solution came from an inventor named Abraham Darby. Born to a Quaker family in 1678, Darby was a metalworker who, after a trip to the Netherlands for some industrial espionage, patented a superior method for casting iron using sand molds. In 1709, at his furnace in Coalbrookdale, he made a pivotal breakthrough: he was the first to successfully smelt iron using "coke" instead of charcoal.

Coke is created by baking coal in an oxygen-starved environment to burn off impurities like tar and sulfur. The result is a fuel that is nearly pure carbon, stronger, more porous, and capable of burning far hotter than charcoal. This innovation was the key that unlocked mass production of iron. It solved the fuel paradox: you could now use a coal-derived product to make the very cookware needed to burn coal in the home.

Forging the Industrial Revolution

The process relied on a blast furnace, where layers of iron ore and coke were superheated. The burning coke released carbon monoxide, which chemically stripped oxygen atoms from the iron ore, leaving behind pure molten iron. This liquid metal would drip down and collect in channels that resembled a sow nursing her piglets, which is why the raw ingots were, and still are, called "pig iron."

Darby's innovation was the critical link. The switch to coal created a demand for better iron pots, and the process of coking coal provided the means to mass-produce them. This feedback loop turned Britain from an iron importer, dependent on well-forested nations like Sweden, into the world's leading iron producer. This cheap, abundant iron would become the essential building block for the machines, engines, and rails of the Industrial Revolution.

Unleashing Steam from Waterlogged Mines (1690 – 1730)

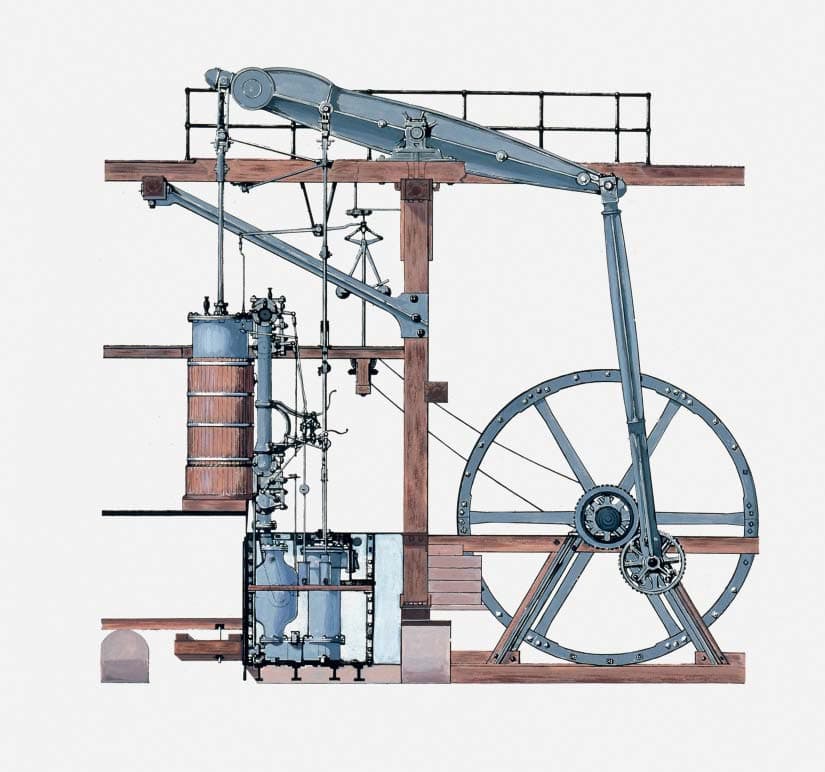

Thomas Newcomen's atmospheric steam engine (1712) was the first practical steam-powered device. Initially used to pump water from coal mines, it enabled deeper mining and launched the age of steam power.

For the first time in history, humans were on the verge of converting heat into motion. Before this moment, if you wanted to move something, you used muscle power—your own or that of an animal. The idea of burning a fuel to create physical force was revolutionary, and its catalyst was a problem created by coal itself: the deeper miners dug for coal, the more they were thwarted by groundwater flooding the mines.

The Miner's Friend

Miners tried everything to dewater the mines. They carried out buckets by hand and dug incredible drainage tunnels, sometimes for miles, that required workers to crawl through spaces no wider than a coffin. By 1700, Britain's dependence on coal was absolute, but its supply was limited by this constant battle against water.

Early experiments by scientists in London's prestigious Royal Society, like Dennis Papin, showed that steam could push a piston, but these were largely theoretical demonstrations. The first practical, if flawed, device came from Thomas Savery in 1698. His machine, called "The Miner's Friend," used steam to create a vacuum that could suck water up about 25 feet. Unfortunately, it required dangerously high-pressure steam and was prone to explosions, making it too risky for widespread use.

Newcomen's Breakthrough

The true breakthrough came not from an esteemed scientist, but from a humble ironmonger named Thomas Newcomen. Born in 1664, Newcomen lived and worked near coal mines, making tools and hearing firsthand about the miners' struggles with flooding. Obsessed with the problem, he teamed up with a plumber, John Cawley, and began tinkering.

Newcomen devised the first atmospheric steam engine. It worked by filling a cylinder with steam to push a piston up. Then, a jet of cold water was sprayed into the cylinder, causing the steam to condense and create a vacuum. The pressure of the outside atmosphere would then push the piston back down, creating a powerful stroke that could drive a pump.

The first Newcomen engine was installed at a coal mine in 1712, and it worked. For the first time, the stored energy in coal was being used to power a machine to do useful work. Though wildly inefficient—it consumed a massive amount of coal—it solved the immediate problem. This set up another classic feedback loop: coal powered the engine that pumped water from the mine, which allowed miners to dig up more coal to power more engines.

Watt's Engine and the Industrial Dawn (1736 – 1800)

Drawing of a Boulton and Watt Rotative engine built in 1784 for the Whitbread Brewery. This is one of three surviving engines of its type—a testament to the partnership that transformed steam power from a pump into a universal prime mover. Courtesy of the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

The Newcomen engine worked, but it was a gas-guzzler. The next great leap required making it dramatically more efficient. That leap came from a brilliant Scottish instrument maker named James Watt. Born in Greenock in 1736, Watt was a gifted craftsman who landed a job at the University of Glasgow, where he befriended leading minds like Joseph Black, the chemist who discovered carbon dioxide, and the famed economist Adam Smith.

A Partnership Forged in Steam

In 1763, the university asked Watt to repair its model Newcomen engine. He quickly realized that three-quarters of the steam's energy was being wasted in repeatedly heating and cooling the main cylinder. His breakthrough idea was to perform the condensation step in a separate chamber, allowing the main piston to remain hot at all times. This single innovation promised a massive increase in efficiency.

Turning this idea into a working machine required capital and manufacturing expertise, which Watt found in Matthew Boulton, a savvy industrialist from Birmingham. Boulton acquired the patent rights to Watt's design and formed one of history's most productive partnerships. Boulton was the sharp businessman Watt was not; as Watt himself confessed, he "would rather face a loaded cannon than settle an account or make a bargain."

The Lunatics and the Boring Machine

Boulton was part of an informal group of Birmingham's intellectual elite called the Lunar Society, who playfully called themselves "lunatics" because they met during the full moon to make their journeys home safer in the unlit streets. Through this network, they found the final piece of the puzzle: an ironmaster named John "Iron Mad" Wilkinson.

Wilkinson had recently invented a precision boring machine to make more accurate cannons. By spinning a solid block of iron and boring a hole through its center, he could create a perfectly straight and smooth cylinder. This was exactly what Watt needed to manufacture a piston that would fit tightly enough to be efficient. Wilkinson's cannon technology unlocked Watt's steam engine.

In 1776, the Boulton & Watt engine was launched. It was four times more efficient than Newcomen's design. Their business model was genius: they charged customers a royalty equal to one-third of their fuel savings for 25 years. Later, Watt developed a rotary motion engine, allowing it to power mills and factories, not just pumps. He also coined the term "horsepower" to measure an engine's output, a unit that, ironically, would one day be replaced by a unit named after himself: the Watt.

The Age of the Railway (1800 – 1850)

Stephenson's Rocket (1829) won the Rainhill Trials and became the template for all future locomotives. It proved that steam railways could reliably transport both goods and passengers, transforming global commerce.

With efficient steam engines and mass-produced iron, Britain was primed for industrial takeoff. But one major bottleneck remained: transportation. Coal is a heavy rock. Moving it by sea was relatively efficient, but moving it over land was prohibitively expensive. In the early 1800s, transporting a pound's worth of coal 250 miles by sea to London might cost two pounds, but moving it just ten miles over notoriously muddy roads would cost the same amount.

George Stephenson, Father of Railways

Early solutions involved digging a massive network of canals and laying wooden or iron rails for horse-drawn carts. The man who would combine rails with steam power was George Stephenson. Born in 1781 to an illiterate coal-mining family near Newcastle, Stephenson grew up fascinated by the pumping engines his father operated. He taught himself to read and write at age 18 and developed a deep, intuitive understanding of mechanics.

After another inventor, Richard Trevithick, built the first, albeit impractical, steam locomotive, Stephenson became convinced he could perfect the design. Backed by a powerful group of mine owners, he built his first locomotive in 1814. It successfully hauled 30 tons of coal up a hill at four miles per hour. Crucially, Stephenson understood that he wasn't just building an engine; he was building a system, pioneering durable wrought-iron rails and establishing the "standard gauge" of four feet, eight-and-a-half inches that is still used on 55% of the world's railways today.

The Rocket and Railway Mania

The first public railway, the Stockton and Darlington line, opened in 1825, featuring Stephenson's engine, named *Locomotion No. 1*. It hauled 80 tons of coal and 600 passengers, reaching a stunning speed of 24 miles per hour—faster than any human had ever traveled in a machine. The true launch of the railway age, however, was the Liverpool to Manchester line in 1830.

For this line, Stephenson and his son Robert built *The Rocket*, a revolutionary design that became the template for steam locomotives for the next century. This railway was the first to be fully steam-powered, double-tracked, and run on a public timetable. The launch was a national event, drawing 400,000 spectators. It kicked off a "railway mania," and within 25 years, Britain had laid over 6,000 miles of track. Coal had finally created a way to move itself, and in doing so, it connected the world in ways never before imaginable.

The Price of Progress (1830s-1840s)

The First Industrial City

With steam engines freed from the rivers and coal now mobile thanks to the railways, the first truly industrial cities could be built anywhere. No city represented this new world more than Manchester. It became a symbol of industrialization, a chaotic nexus where cotton shipped from slave plantations in America met coal from nearby mines.

This created a powerful feedback loop: bigger steam engines fueled bigger factories, which demanded bigger workforces, creating ever-bigger cities. By the 1830s, Manchester had seven cotton mills with over a thousand workers each. The French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville visited in 1835 and was stunned by the paradox of the city. "From this foul drain," he wrote, "the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilize the whole world. From this filthy sewer, pure gold flows."

The 24-Hour Factory

A surprising byproduct of coal accelerated this brutal efficiency: coal gas lighting. When coal is heated to make coke for iron smelting, a flammable gas is released. Previously wasted, this gas could be captured, piped, and lit, providing a cheap and bright source of light. By 1805, coal gas was keeping factories illuminated around the clock, allowing mill owners to run their expensive machinery 24/7.

The machine now set the pace of life. As one contemporary observer wrote, "While the engine runs, the people must work. Men, women, and children are yoked together with iron and steam." This relentless pace, combined with horrific urban conditions, took a devastating toll. In 1842, a government report found that 57% of children born to the laboring classes in Manchester died before the age of five. Rickets, a bone-deforming disease caused by a lack of sunlight from smoke-filled skies and endless factory hours, became known as "the English disease."

A Revolutionary Idea

Ironically, one of the factory owners was a bit of a radical. A young German named Friedrich Engels was sent by his family to Manchester to learn about their cotton mill business. Engels, however, was far more interested in the condition of the workers than the efficiency of the mill. In 1845, he published his blistering critique, *The Condition of the Working Class in England*.

Around this time, Engels began a fateful partnership with another German thinker, Karl Marx. Together, they channeled their observations of industrial capitalism into the *Communist Manifesto*, published in 1848. In a twist of history, the wealth Engels' family extracted from the coal-powered Manchester mills would directly finance Marx's work for decades, spreading an ideology born from the economic divisions forged in the heat of the Industrial Revolution.

Life in the Darkness (1700s-1842)

Lewis Hine's photograph of child coal miners captures the brutal human cost of the coal economy. Boys as young as 8 worked in dangerous conditions for pennies a day.

The Outcasts

While factory workers faced new forms of hardship, an older class of laborers endured conditions that were arguably worse. Coal miners were often treated as social outcasts, a separate species bred for the darkness. Yet this isolation forged a powerful sense of camaraderie, an experience akin to soldiers in the trenches, as they faced astonishing dangers to provide the nation's vital fuel.

Mining was a family affair where men hewed the coal while women and children hauled it to the surface. In some feudal systems, families were treated as property, sold along with the mine itself. It was almost certainly the most perilous profession of the era, a workplace where multiple invisible forces were trying to kill you at any given moment.

The Damps and the Dark

Miners gave names to their invisible enemies. "Choke damp" was a dense cloud of carbon dioxide that could suffocate a man instantly. "White damp" was carbon monoxide, a deadly byproduct of underground fires, which led to the practice of bringing canaries into the mine as an early warning system.

The most terrifying was "fire damp"—methane gas that seeped from the coal seams. As miners needed open flames for light, a single candle in the wrong place could trigger a massive explosion, killing everyone in the pit. This led to the insane job of the "fireman," who would crawl along the floor in soaked rags, using a long pole with a candle to intentionally set off small, controlled explosions. These disasters were so frequent that local newspapers often stopped reporting them.

The Children of the Pits

The hardest part of this history to confront is the role of children. Because many coal seams were too narrow for adults or carts, children were essential for hauling coal and manning ventilation doors. Children as young as five, and sometimes even three, worked 12-hour shifts, often in total darkness, from before sunrise to after sunset, never seeing the sun for six days a week.

In 1838, a flooding accident at a mine killed 26 children, sparking a rare moment of public outrage and an inquiry led by Lord Ashley. The testimony he gathered was horrifying. Eight-year-old Sarah Gooder, a "trapper" who opened and closed ventilation doors, said, "I have to trap without a light and I'm scared... I dare not sing in the dark." If she fell asleep, everyone could die.

The testimony of 17-year-old Patience Kershaw was even more shocking. She described wearing a belt and chain to haul coal carts, working alongside naked men who would "take liberties." The combination of child labor and Victorian moral outrage finally led to the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842, which outlawed the employment of women and girls underground and set a minimum age of 10 for boys. But with only one inspector for the entire country, the law was barely enforced for decades.

An American Awakening (Early 1800s)

A Land of Wood

While Britain choked on coal smoke, a new nation was being forged across the Atlantic on the seemingly limitless energy of wood. Early colonists arriving in North America found a continent "wooded to the brink of the sea." For settlers accustomed to England's dwindling forests, this was paradise. "Here is good living for those that love good fires," one pamphlet advertised.

Hidden beneath this astonishing wealth of timber, however, lay one of the world's richest coal deposits, including a single coalfield half the size of Europe. But with so much wood available for fuel, construction, and export, there was little incentive to dig for the black rock. For its first centuries, America was a nation powered by its forests.

The Mountain on Fire

As legend has it, the great awakening happened by accident. A hunter named Necho Allen, camping in the mountains of eastern Pennsylvania, built his campfire on a ledge of rock and fell asleep. He awoke in alarm to find "the mountain was on fire." He had unknowingly built his fire on an outcrop of anthracite, a hard, shiny form of coal that came to be known as "stone coal."

This discovery revealed America's unique geological gift. The Appalachian Mountains cleanly divided two different types of coal. To the east, near Philadelphia, lay the difficult but clean-burning anthracite. To the west, around a new settlement named Pittsburgh, lay the dirty but powerful bituminous coal that had fueled Britain's rise. This geographic split would shape the nation's industrial development.

A Forcing Function

At first, anthracite proved incredibly frustrating. It was so dense and difficult to ignite that early shipments to Philadelphia were dismissed as useless and used as gravel for sidewalks. One frustrated customer declared, "If the world should take fire, the Lehigh coal mine would be the safest retreat, the last place to burn."

The catalyst for change was the War of 1812. Before the war, coastal cities like New York and Philadelphia imported much of their coal from Britain. When war broke out, the British Royal Navy—itself a product of the coal trade—blockaded American ports, cutting off the supply. Suddenly faced with an energy crisis, the industrializing North was forced to figure out how to unlock the power of its own "stone coal."

King Coal and the Civil War (1820s-1876)

American Mania

Entrepreneurs like Joseph White and Erskine Hazard finally cracked the code of transporting and burning anthracite. By 1822, they had formed a company to navigate the treacherous rivers from the mines to Philadelphia. Soon, the canal mania that had swept Britain arrived in America. The Delaware and Hudson (D&H) Company built a canal system to bring Pennsylvania coal to New York City, completed in 1828.

Mirroring the excitement in Europe, the D&H public offering was a massive success, selling 1.5 million shares in a single afternoon from a New York coffee shop. Soon after, rail mania also crossed the Atlantic. However, America's first trains ran on an abundant local fuel: wood. These early locomotives were notorious for setting fire to everything around them—fields, forests, and even the flammable dresses of their passengers.

The First Villain

As infrastructure improved, the power to control coal shifted to those who controlled its transport. This era produced one of America's first great corporate titans, Franklin Benjamin Gowen. A sharp lawyer who became president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad in his early 30s, Gowen saw the power of vertical integration. He cleverly bypassed a state law to allow his railroad to begin buying up the very anthracite mines it serviced.

In 1873, Gowen assembled a cartel of all the major coal operators to control prices, squeezing both consumers and miners. When miners tried to unionize, he fought back with a ruthless PR campaign, hiring secret agents to infiltrate their ranks and fabricating a story about a secret Irish terrorist group called the "Molly Maguires." Acting as a special prosecutor, Gowen personally led the murder trial that broke the union, cementing the public image of organized miners as violent radicals.

Gowen's empire eventually crumbled under financial overextension, forcing the railroad into the hands of the banker J.P. Morgan. But his reign had established the powerful and often brutal link between coal, railroads, and finance that would define the Gilded Age, and his name was once as famous as those of Carnegie or Rockefeller.

A Nation Divided by Energy

By the mid-1800s, this wave of coal-powered industrialization had transformed the American North, while the South remained an agrarian society built on slave labor. This growing economic and technological gap set the stage for the Civil War. While the South declared that slavery was "the greatest material interest of the world," it completely missed the true material unlock happening just up the road in Pennsylvania.

The North's industrial advantage was overwhelming: 15 times more iron production, 32 times more firearms production, and a staggering 38-to-1 advantage in coal. This energy supremacy fueled the Union's factories, railways, and steam-powered navy, playing a decisive role in its victory. President Lincoln understood this, famously remarking of the coal-rich border state Kentucky, "I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky."

Conclusion

Global coal consumption continues to rise, with 2023 marking the highest usage in human history. Coal remains the largest single source of CO2 emissions worldwide.

The Scale of Transformation

By 1876, at the nation's Centennial celebration in Philadelphia, the transformation was complete. America, once a collection of wooded colonies, now stood as an industrial superpower, the new "workshop of the world." The Machinery Hall at the exhibition, a 14-acre testament to steam and iron, showcased a nation that had fully embraced the power of coal.

The pace of this change was breathtaking. Coal consumption in the United States doubled every decade from 1860 to 1900. While wood still provided more energy than coal in 1876, the future was clear. By the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. would be producing more coal than Britain, Germany, or any other nation on Earth, setting the stage for the American Century.

A Problem, and its Own Solution

The story of coal's rise reveals a fascinating pattern: the fuel created problems that it then helped to solve. The difficulty of hauling coal was a massive drawback, but the desperate need for a solution spurred the invention of the steam locomotive and the modern railway—a system powered by the very coal it was designed to transport.

This feedback loop had revolutionary consequences far beyond the coal industry itself. Once built, the railways didn't just move coal; they moved people, mail, food, and ideas. They connected cities, created national markets, and fundamentally altered the human relationship with time and distance. The solution to coal's logistical problem reshaped the world.

The Stage is Set

The Shuozhou coal-fired power plant in Shanxi Province, China. Despite global climate commitments, massive coal infrastructure continues to be built and operated worldwide.

As the 19th century closed, all the pieces were in place. The steam engine could provide power anywhere, freed from the constraints of wind and water. The railway could move fuel and goods across vast continents. Sophisticated mining techniques could extract coal from deep within the earth. For the first time, humanity had access to a seemingly limitless, mobile, and on-demand source of energy.

This new reality unlocked the potential to build truly industrial cities and laid the foundation for the central conflicts of the 20th century—from ideological battles born in the Manchester mills to the industrial warfare powered by the coalfields of Pennsylvania and beyond. The age of wood was over. The age of coal had arrived, and with it, the modern world.

Thanks for listening and learning with us. Drop us a note with thoughts or feedback anytime.

— Ben & Anay

hi@stepchange.showExplore the Data

Interactive charts showing coal production, consumption, and emissions from the Industrial Revolution to today's energy transition.

The rise and evolution of global coal production from the start of the Industrial Revolution to today, measured in terawatt-hours.

Source: Our World in DataContinue the Story

The story of coal did not end in 1900. Ahead lie the World Wars, the rise of electricity, the emergence of new industrial giants like China and India, and the dawning awareness of coal's impact on our planet's climate.

Sources & References

- Barbara Freese (12/12/24)

- Johnston Suter (1/6/24)

Geological History

- The Carboniferous Period (Wikipedia)

- Earth's Historical Timeline Visualization

- Coal-Bearing Areas of the United States

- USGS Coal Resources and Historical Production

- Coal Mining Regions (Wikipedia)

Industrial Development

- British Population Growth (1100-Present)

- The Industrial Revolution (Wikipedia)

- History of the Steam Engine (Wikipedia)

- Newcomen Atmospheric Engine (Wikipedia)

Key Historical Figures

- Abraham Darby I (Wikipedia)

- James Watt (Wikipedia)

- Matthew Boulton (Wikipedia)

- John Wilkinson (industrialist) (Wikipedia)

- George Stephenson (Wikipedia)

- The Lunar Society of Birmingham (Wikipedia)

- The Grand Allies (Wikipedia)

- Friedrich Engels (Wikipedia)

- Coal Mining Labor Practices and "Hurrying" (Wikipedia)

- Lord Ashley and Labor Reform

- Franklin B. Gowen (Wikipedia)

- The Great Smog of London (1952) (Wikipedia)

- The Centralia Mine Fire (Wikipedia)

- Pennsylvania Anthracite Mining History (Wikipedia)